Posted on November 16 2022

By Staff writer for Classic Cars on April 23

[Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Classic Motorsports.]

Why are Cobras worth so much? Simple: because you and everyone else wants one. Fortunately, there’s a more cost-effective substitute, the Sunbeam Tiger. What’s a Tiger? It’s the Cobra’s formula applied to another small British sports car, the Sunbeam Alpine. The Cobra and the Tiger prototype were even built by the same irascible Texan, Carroll Shelby. Tigers are considered the more comfortable and refined of the two, so they’re perfect for road rallies and weekend drives. Plus, they’re more than affordable compared to a million-dollar Cobra: A nice Tiger can be had for a touch more than $50,000.

“Great,” you’re probably thinking, “I’ll fire up eBay Motors and buy one.” Not so fast. You’ve got a big decision to make.

Tigers can be split into three very distinct groups: early cars, worth as much as $118,000 according to Hagerty; late cars, worth as much as $205,000; and transition cars, worth somewhere in between. Why the difference in value? Is a late Tiger really twice as good as an early one? We drove two concours-correct examples owned by Kim Barnes to find out.

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe

The Tiger’s first model year was 1964, but its story starts with the Sunbeam Alpine, which went on sale in 1959. The Alpine was a better-built competitor of the Triumph TR3 and MGA. Rootes Group, Sunbeam’s parent company, created it to capture the huge demand for British sports cars in the United States. The car had a few tricks up its sleeve to win America’s attention, like roll-up windows, disc brakes and unibody construction. Unfortunately, Sunbeam was late to the game. By the time the heavier, slower Alpine became available, many buyers had already made up their minds and bought Triumphs, Austin-Healeys and MGs. Alpines weren’t bad cars, but they weren’t terribly exciting–and neither were their sales. Until Ian Garrad came along, that is.

Catch a Tiger by the Toe

Garrad headed Rootes Group’s West Coast distribution, and he had an idea to revitalize the Alpine: Shove Ford’s new 260-cubic-inch V8 under the hood. Garrad commissioned two prototypes, one to be built by Ken Miles of Shelby American and another by Shelby American proper. Miles, whose objective was to simply find out if the swap was feasible, hastily finished his version in a few weeks. Unlike the eventual production car, his prototype was cheap and crude: It sported a two-speed automatic, kept the Alpine’s recirculating ball steering, and was basically just bodged together.

This down-and-dirty prototype was fantastic, at least in Garrad’s mind, since it proved his concept had legs. Of course, once the second prototype came out, it quickly became the star. After spending considerably more money and time, Shelby American unveiled a fairly polished V8-swapped Alpine, this time with rack-and-pinion steering and the four-speed manual that would eventually make its way to the production line.

Garrad finally felt confident enough to tell the company chairman about his experiment, so he headed over to England to let Lord Rootes himself take a spin in the V8 Alpine. Rootes loved it and called Henry Ford to order lots of V8 engines. Now, you’re probably expecting to read about how Shelby’s prototype was further polished into a production-ready automobile before its debut for the 1964 model year. Fun fact: It wasn’t.

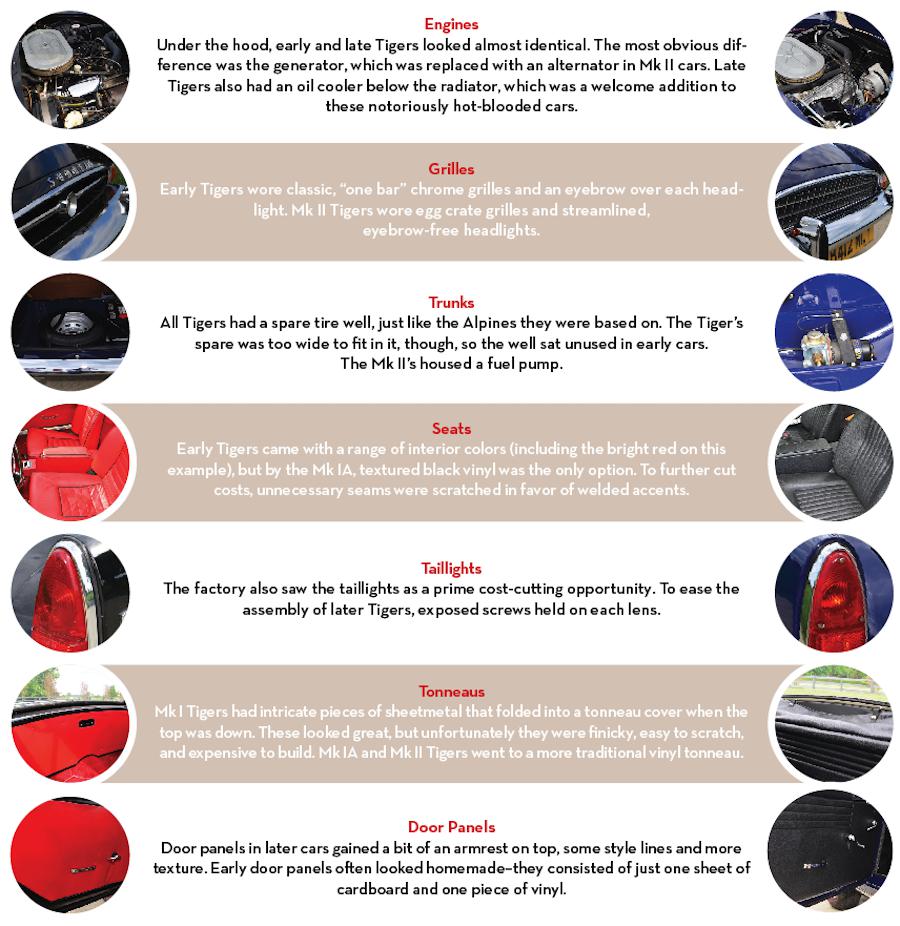

Tigers can be divided into two basic groups: Mk 1 (black) and Mk 2 (blue).

To produce Tigers, Sunbeam basically sent Alpine bodies down a production line full of hammers, stick welders and V8 engines. The easiest way to spot a fake Tiger? Look for quality workmanship, since real Tigers emerged from the factory sporting a slew of dents, cuts and nasty-looking welds. Chassis modifications that weren’t for the sole purpose of shoehorning the V8 under the hood were few and far between. Tigers even shared the Alpine’s brakes.

The Tiger was released in the last gasp of the British automobile industry, and it valiantly dug in its claws and held on as long as it could during Rootes Group’s transition to Chrysler. Although it couldn’t halt the decline of its parent company, it did manage to remain an enthusiast favorite for decades to come.

Tiger Timelines

One car model’s fight in a flailing industry.

Mk I Driving Impressions

Let’s just say this right out of the gate: If you’re going to buy a MkI Tiger and plan to leave it stock, don’t read any period reviews. Just don’t. Put down that vintage issue of Autocar, and especially avoid the part where they write, “The Tiger is a rapid and exceedingly enjoyable car to drive.”

Why? In all honestly, early Tigers are fairly slow by modern standards. In 1964, a 2500-pound car with 164 horsepower was unheard of, but these days a Miata will destroy one in a straight line. In the corners, well, let’s not talk about corners. Tigers handle like derailed trains, and sound about the same while they’re doing it.

What early Tigers are best at, instead, is touring. They’re a gentleman’s sports car, but the Alpine’s wheezy four-banger everyone expects is replaced with a docile, torquey V8. They’re cars you could spend all day in, and build quality and comfort are definitely a notch or two higher than the average Triumph.

1964 Sunbeam Tiger MK I Specifications

• Layout: Front engine, rear-wheel drive

• Transmission: 4-speed manual

• Engine: 260-cu.-in. V8

• Suspension: Double wishbone front, live axle w/Panhard bar rear

• Tires: 5.90x13 in.

• Wheels: 13x4.5 in.

• Brakes: 9.85-in. discs front, 9-in. drums rear

• Horsepower: 164 @ 4400 rpm

• Torque: 258 ft.-lbs. @ 2200 rpm

• 0-60 mph: 9.5 sec.

• Weight: 2525 lbs.

• Length: 156 in.

Mk II Driving Impressions

Comparing engine displacements can be deceiving. Take the early Tiger’s 260 cubic inches versus the later car’s 289. What’s 29 cubic inches really worth? It’s basically like bolting a lawn mower engine on top of a Mk I Tiger’s, right? Well, no.

In fact, the 289 is transformative. That 36 extra horsepower and 24 extra ft.-lbs. of torque somehow turn the knobs to 11, making the Mk II Tiger feel legitimately fast. The numbers back that up, too: Zero to 60 in 7.5 seconds allows this one to keep pace with most modern sports cars, though it only runs a 15-second quarter mile. From the driver’s seat, the other noticeable difference between the two cars is ventilation. Mk IA and Mk II Tigers have cowl vents that make them much more comfortable on hot summer days.

Is the drop in build quality noticeable? We think so. Call us old-fashioned, but we love the leaded body seams and rounded corners that make the earlier Tigers such a pain to assemble and restore. And although the Mk II’s vinyl tonneau is much more functional, the Mk I’s impractical metal version is so nice to look at.

1967 Sunbeam Tiger MK II Specifications

• Layout: Front engine, rear-wheel drive

• Transmission: 4-speed manual

• Engine: 289-cu.-in. V8

• Suspension: Double wishbone front, live axle w/Panhard bar rear

• Tires: 5.90x13 in.

• Wheels: 13x4.5 in.

• Brakes: 9.85-in. discs front, 9-in. drums rear

• Horsepower: 200 @ 4400 rpm

• Torque: 282 ft.-lbs. @ 2400 rpm

• 0-60 mph: 7.5 sec.

• Weight: 2560 lbs.

• Length: 156 in.

Having started Legend Lines by designing the Cobra, it was logic to design the other Carroll Shelby's Legendary car: The Sunbeam Tiger, the other little British automobile. If I remember well, she stood in the 20th first designs.

0 comments